Hurricanes Left Tampa Bay’s Immigrant Community Reeling. Here’s How Some are Recovering.

Nancy Guan | WUSF

Dec 18, 2024

A vibrant immigrant community in Clearwater experienced some of the worst flooding in the area. Local groups are stepping in to ensure they’re getting the right resources.

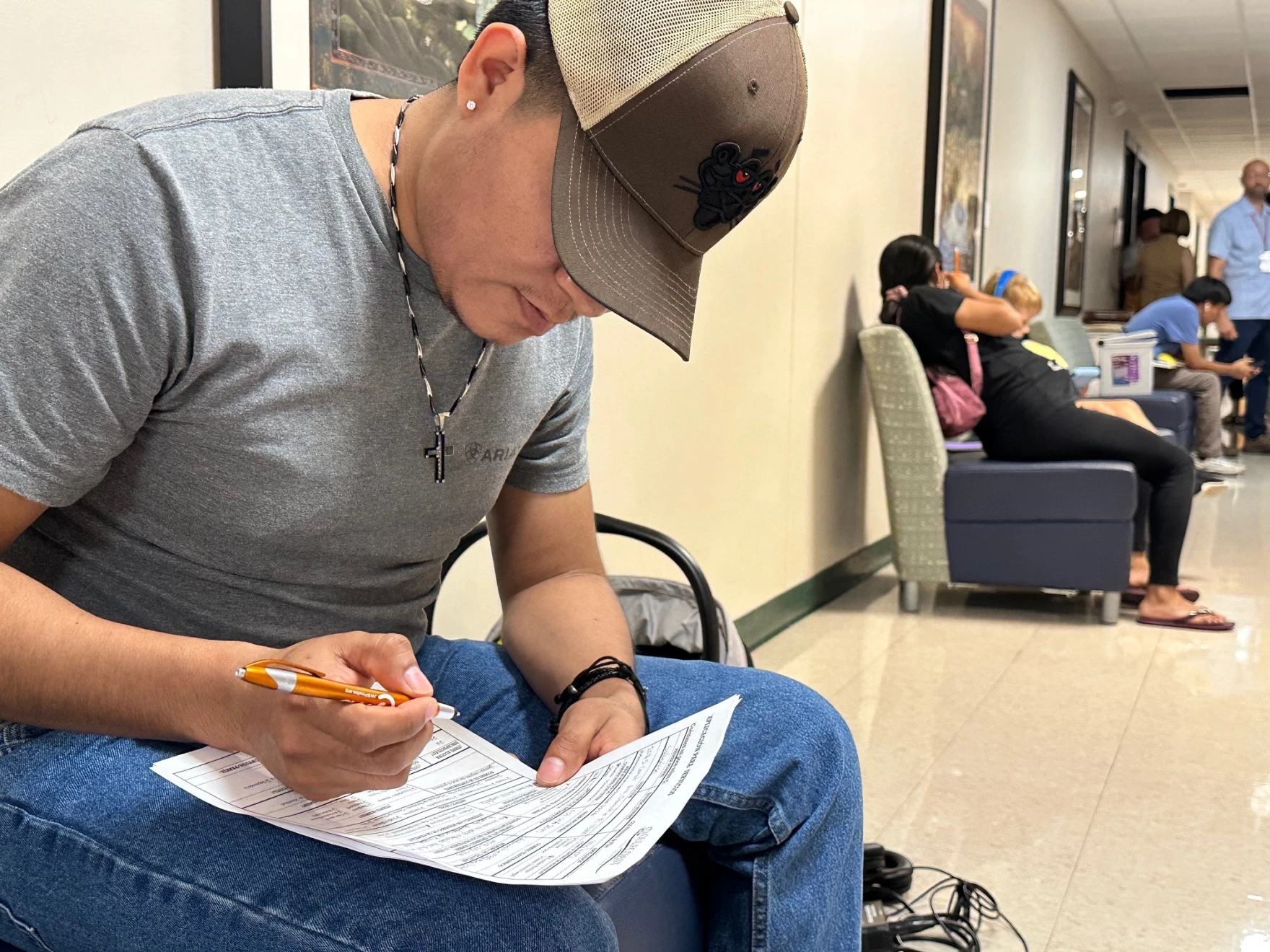

In the crowded halls of St. Petersburg College’s Clearwater campus, a young father sits with his head down, filling out a hurricane relief form.

“Prácticamente todo este lo perdí ahí durante el huracán (I lost practically everything in the hurricane),” he said.

He’s asked WUSF to call him by his nickname Matias because he’s in the country without documentation.

Matias is one of hundreds of Standard Apartment residents who lost their home to floodwaters from Hurricane Milton, one of the worst storms to hit the Tampa Bay region in a century.

Even though the complex itself isn’t in a flood zone, residents there say they’ve always had flooding issues. The area is shaped like a bowl, according to community advocates. And during Milton’s downpour, a nearby pond overflowed and burst through a retention wall.

More than 500 residents had to be rescued that night.

Matias returned home in the early morning hours on Oct. 10, and found that four feet of water filled his apartment.

“Anything touching the floor, my shoes, my clothes were all wet,” he said. “Even my car, all of my tools for work, everything was gone.”

Matias works as an electrician about 40 minutes away from home. He’s been making due driving a relative’s car and had to buy a new set of tools in order to continue making a living.

He, his wife and three-month old son have been couch surfing with friends and family, which he’s thankful for, but it’s getting harder to manage each day, he admits.

That’s why he’s come to the college campus this Thursday night where several local nonprofits have set up a legal aid clinic. Here, he’s able to receive help in Spanish and ask what resources are available to him.

For those like Matias, options are limited. Four years ago, he crossed into the U.S. through the southern border from Mexico. He doesn’t have a Social Security number or legal work authorization, barring him from receiving federal aid like FEMA or unemployment benefits.

For now, he hopes to rely on local charities and aid groups. Matias was able to submit a FEMA application on behalf of his three-month old son, who was born here, but is still waiting on a response.

Because of his immigration status, he was wary of accepting help from certain groups. The American Red Cross, a humanitarian organization that helps people through natural disasters, offered shelter to residents after Milton hit.

“No había mucha confianza. (We didn’t have much trust in going there),” said Matias.

And they weren’t the only ones who felt that way.

“While I didn’t live through the flood, my friends, they lost everything. And they risked their lives that night. I can’t imagine how they lived through that moment.”

Officials with local nonprofits that had stepped in to help after the storm said they witnessed multiple families who refused assistance and shelter because they were afraid government agencies would take down their information.

“They were taken by a bus to an unfamiliar location, and it looked very intimidating and institutional,” said David Hale, executive director of Mattie Williams Neighborhood Family Center, which serves the Clearwater area. “So the lack of communication and the lack of cultural understanding resulted in a failure there to provide the emergency services.”

Some who couldn’t find shelter with friends or family returned to water-logged homes that had no running water or electricity.

“We found families with small children and infants living in those conditions. It was the only choice many of them felt they had,” said Hale.

‘Like a bomb exploded’

Karla is another former Standard resident who lost her second floor apartment due to mold that crept up from the unit below. We’re not disclosing her last name since she is also undocumented.

Karla came to the U.S. from Mexico over 20 years ago for more opportunities for herself and for her children, she said. She and her husband lived in the Clearwater complex for over a decade raising their two daughters.

Familiar with the area’s flooding issues, her family stayed with friends the night of the hurricane. When they returned several days later, Karla couldn’t believe the destruction.

“It was like a bomb exploded and destroyed everything,” she said through a translator.

Piles of furniture and household goods were strewn outside. Broken glass littered the patios where floodwaters surged into first floor apartments. Early memories of her children playing in the complex welled up, and Karla became emotional.

“While I didn’t live through the flood, my friends, they lost everything. And they risked their lives that night. I can’t imagine how they lived through that moment,” she said.

Outside their apartment door, on the second floor, lay a child’s life jacket and a package of cookies, said Valeria, Karla’s daughter.

“You can tell someone had spent the night there,” she said.

Karla understands why people are afraid to seek help. As an immigrant, “you’re afraid that you’re going to be asked for a document, for a piece of paper, or for a number. Sometimes that fear is justified, sometimes it comes from a lack of knowledge.”

After decades of living in the U.S., Karla said she’s learned how to navigate the risks.

“I was always interested in learning what I could do for myself, for my children and family. Even though I am an immigrant, I have rights as a human and as a person,” she said.

Her children are U.S. citizens so they were able to apply for FEMA aid for the family. And her daughter works for a church that hosted one of the Red Cross shelters in the first few weeks after Hurricane Milton.

“We told people we were going to be taking them to the church, that there was food, that there was shelter, and, really, just trying to change the narrative — that that was a good option.”

Amanda Markiewicz, Hispanic Outreach Center

The two had returned to The Standard Apartments to try and convince some of the families there that those resources were safe.

But what they found was that “a lot of them were just not wanting to go, not wanting to accept the help,” said Valeria.

And it’s not hard to imagine why. Valeria explains, “there’s that fear, you know, I guess you kind of risked everything to come here. Now they can easily take that away from you — that kind of fear.”

Local aid groups step in to help

Amanda Markiewicz is with the group Hispanic Outreach Center, a nonprofit that has been in the community for over twenty years.

“In a time like this, there’s a lot of barriers for anybody. When you add in limited English, or you add in immigration status, or you add in multiple people in a home that might not be on a lease, it opens up for a lot more barriers,” said Markiewicz.

The Center partnered with other trusted groups like Mattie Williams Neighborhood Family Center to canvas the area.

“We told people we were going to be taking them to the church, that there was food, that there was shelter, and, really, just trying to change the narrative — that that was a good option,” said Markiewicz.

“We have staff who are dedicated to providing services to these communities and understand the dynamics and the barriers that they face on a day-to-day basis, let alone with a crisis.”

Markiewicz said they were able to quell some of the worries residents had. They even organized transportation from the shelters to schools for families who had school-aged children.

“It was a lot of coordinated effort that took place,” said Markiewicz.

But the road ahead for many of these families is a long one.

About half of The Standard Apartment’s nearly 500 units were affected by the storm. Most residents are looking elsewhere for housing, afraid that another disaster like this could hit again next year.

Karla and her family are staying with a friend, and are in the midst of their search for a new home. But rent is high, especially with so many other victims of the hurricane looking for a new place.

Valeria said she’s picked up a second job working retail. Her younger sister is in college, so she’s also helping to pay for her tuition.

Matias finishes filling out his form in the noisy hallway. He hopes that some aid will come to his family, mainly because he has to take care of his child. While they’ve lost almost all their belongings, he says those “material things can be replaced.”

“Tenemos salud y eso es lo importante (We have our health and that’s the most important thing),” said Matias.